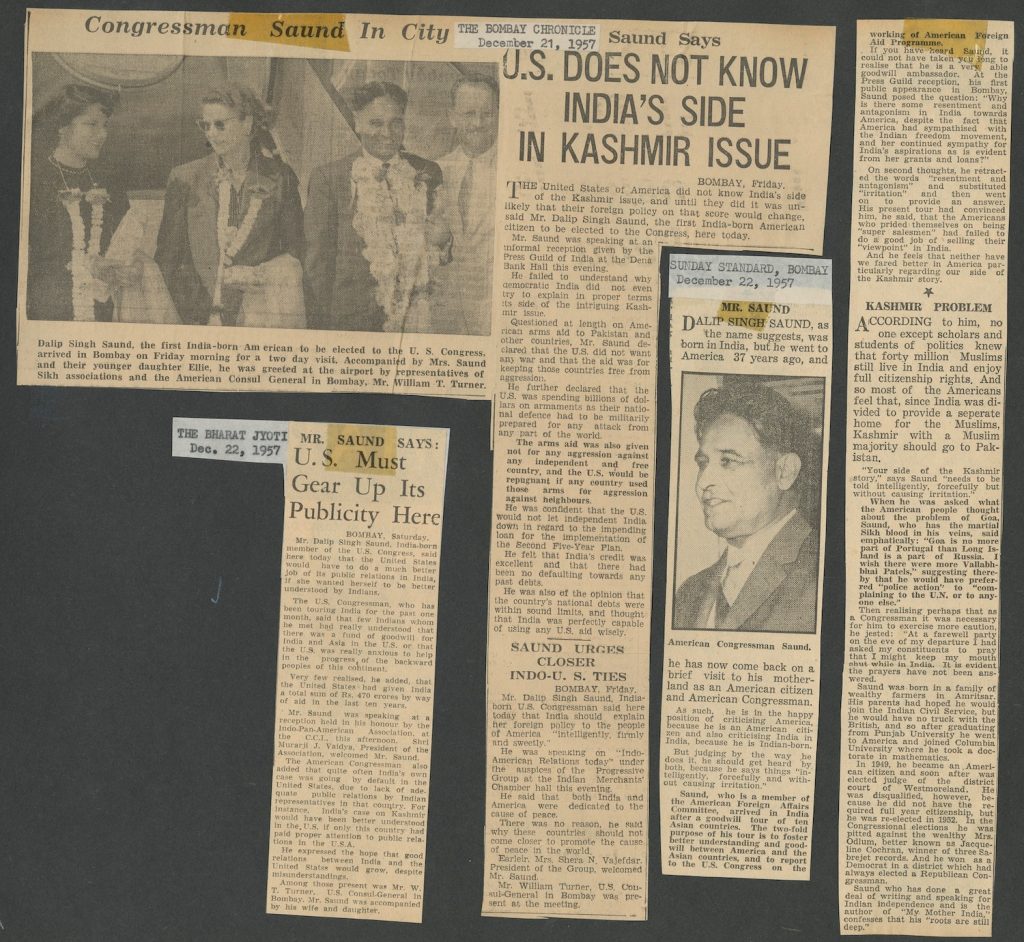

A December 21, 1957 article in The Bombay Chronicle entitled “Congressman Saund in the City” covers Dalip Singh Saund’s return tour to India. Saund is greeted at the Bombay airport with malas, or flower garlands, and his family members are honored by a single mala each for accompanying Saund. The malas represent the respect Indians have for Americans and Saund’s success in the U.S. When looking at the photograph of Saund sporting layers of malas during what 1957 coverage in The Sunday Standard referred to as his “goodwill tour” and return to India, I became curious about the surge of pride and respect represented by these tokens. The Sikh associations and American Consul General’s warm greetings with malas illustrate the multiple facets of Saund’s identity. He returns to India as the son of India but is greeted as a U.S. Congressman. Yet, Saund, being both Indian and American, is respected for his success as an Indian in the U.S. and for substantiating Indian and American relations. This coverage of his tour asks us to think about how Saund pressures India to understand the beneficial relationship between the East and West that he embodies as an advocate—what The Bombay Chronicle frames as “closer ‘Indo-U.S. ties.” Saund’s return to India as a mediator between India and the U.S. does not fulfill the symbolic alliance illustrated in his rhetoric. Instead, Saund’s complicated homecoming reveals his diasporic identity as a political expediency, and his prioritization of his American identity represents the uneven power dynamics between India and the U.S.

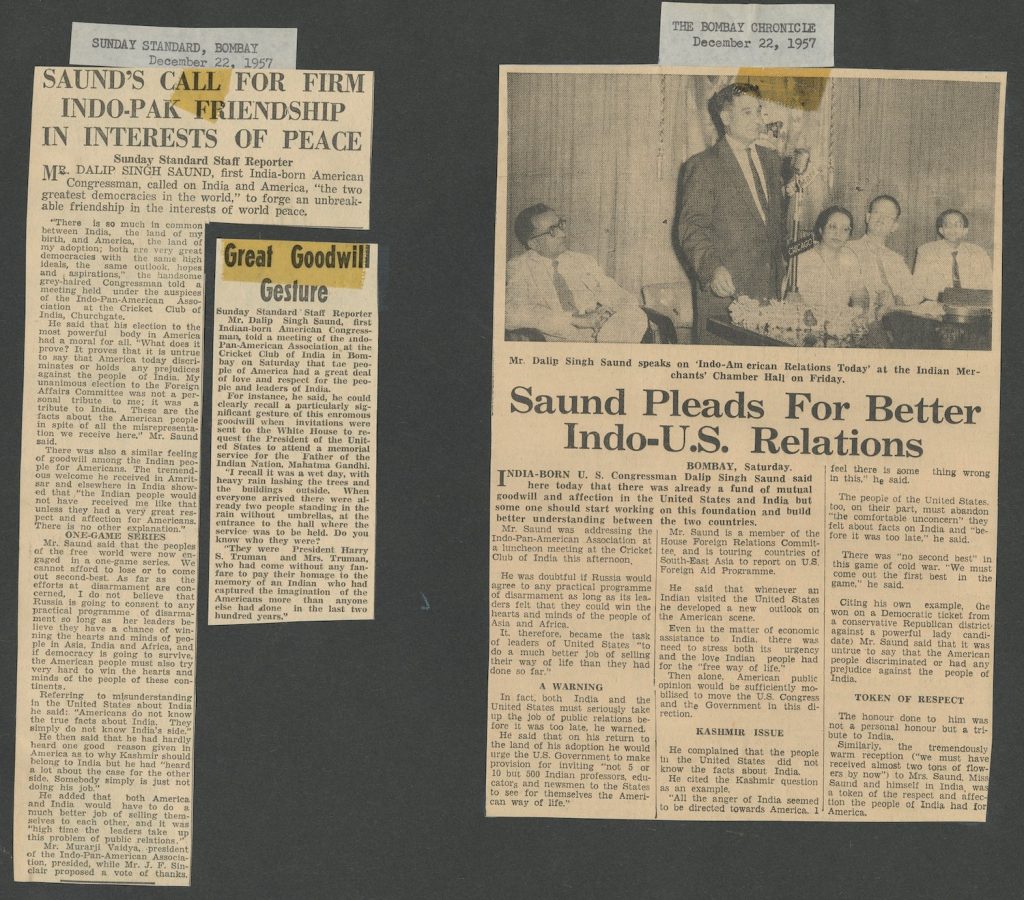

Pasted next to The Bombay Chronicle coverage of Saund’s arrival in Bombay, an article from the Sunday Standard features a solo photograph of his face, subtitled “American Congressman Saund.” He is given a literal spotlight which causes his skin to glow. This spotlight belongs to the American Congressman, not just any son of India. For the Indian audience of the image, Saund is primarily known as “an American citizen and American Congressman.” Unlike other solo photographs of Saund, this image has a simple background. He is looking away, possibly talking to someone, or giving a speech, and doing his job. For an Indian audience, there is no need for a background that may give further context as to Saund’s importance; his being a U.S. citizen and his success as a Congressman alone suggest the apparent inclusivity of American democracy. Saund embodies American democracy as a model figure of a model nation.

Saund’s tour is posed as a “great goodwill gesture” where he not only advises alliance between India and the U.S. but also suggests idolization of the U.S. Another article in The Bombay Chronicle from December 22, “Saund Pleads for Better Indo-U.S. Relations,” shows Saund standing and giving a speech with the malas near him but off his neck. Malas are often gifted to important figures, but the removed malas suggest that his Indian audience is as significant as him. Yet, his counterparts look up at him while they are seated; he looks down with ease while the others uncomfortably tilt their heads upwards as he speaks above them. At the focal point of these homecoming gatherings, Saund illustrates his complicated positioning. Despite his attempts to align himself with the people, he is a spokesman for the United States’ position in the Cold War and presents the U.S. as an example that postcolonial India is advised to follow. Saund’s focus on being a representative of U.S. democracy prevents him from properly addressing India’s postcolonial concerns. The article’s headline claims that Saund “Pleads” for “Better Indo-U.S. Relations,” but he more so urges India to look up to the U.S. much the way that his Indian audience looks up to him while he speaks.

Saund’s suggested “goodwill gesture” is a push for the development of an Indian democracy in an American trajectory. Next to photographs of Saund’s tour, the newspaper article, “U.S. Does Not Know India’s Side in Kashmir Issue,” presents U.S. sympathy towards India. The Sunday Standard coverage describes how Saund questions “the resentment and antagonism in India towards America, despite the fact that America had sympathized with the Indian freedom movement,” and he says, “her continued sympathy for India’s aspirations . . . is evident from her grants and loans.” He talks of the U.S. as a woman, perhaps a mother figure who can support “her” struggling child—India. In articles covering his homecoming and elsewhere, Saund often describes mother U.S. as “fair.” His words encourage India to reciprocate a democratic sense of fairness and sympathy by aligning with the U.S. For a newly independent India, one solution to calm postcolonial tensions, as Saund suggests, is loyalty to the U.S. and the adoption of an American sense of democracy in return for “armaments.” In Saund’s lexicon, his encouragement to politically align is the definition of “goodwill,” but alliance with the U.S. does not consider India’s oppressive behavior towards Kashmir nor the history of conflict within South Asia.

The Sunday Standard coverage of Saund’s tour suggests that U.S. grants and loans are compatible with the Indian occupation of Kashmir. This aid supports India’s position in the conflicts among South Asian countries. However, Saund is unable to recognize how increasing Indian militarization would further complicate India’s political conflicts. The unknown journalists who report on Saund’s proposition regarding “India’s Side in Kashmir Issue” might well be skeptical as to how much the U.S. Congressman understands Indian politics. Saund’s manner implies that India’s standpoint regarding Kashmir “needs to be told intelligently, forcefully but without causing irritation.” He urges democratic, fair, and respectful behavior when communicating with the U.S. so that alliance can benefit both countries but fails to recognize the contradiction of militarization, which would likely increase conflicts in India, Kashmir, and among neighboring countries rather than decreasing conflicts as the alliance proposes. Saund’s “goodwill” suggests violence as a solution which is harmful to Kashmir and unprogressive for a postcolonial India.

Referring to Saund’s speech at the Press Guild of India, The Bombay Chronicle reports that Saund “failed to understand why democratic India did not even try to explain in proper terms its side of the intriguing Kashmir issue.” While Saund feels that the U.S. is willing to listen to Indian perspectives, the journalist writing this piece appears to disagree, implying that it is Saund, the middleman between India and the U.S., who has “failed to understand” Indian perspectives. Additionally, the journalist recognizes India as “democratic” while Saund only speaks of democracy as a possession of the U.S. India cannot imitate American democracy because the U.S. does not address Indian postcolonial needs and desires. Saund idolizes the United States’ position in the alliance which is why his “goodwill” actions feel insincere.When is Saund as a diasporic Indian concerned about the postcolonial conditions of his home in India and when is he, as a U.S. Congressman, doing his job? Saund fails to present himself equally as a son of India and an American Congressman because the U.S. is his priority—illustrating that the East and West do not meet with the ease that Saund suggests. Saund’s homecoming complicates the simplicity of his discussion on his ethnic, national, and political positions. While the purpose of his alternation between Indian and American identities is to mediate conflicts among India and the U.S., the alternation becomes a site of conflict and tension instead. Saund’s switch between Indian and American identities is unsuccessful because of his focus on encouraging “Indo-U.S. Relations” more than addressing Indian concerns. The U.S. Congressman pressures India to side with the U.S. and accept the U.S. as a role model, embodying U.S. imperial values. While understanding the consequences of British colonialism, Saund advocates for India’s authority over Kashmir. Saund, a propagandist of American democracy, admires the United States’ fairness, yet his support of India’s control over Kashmir demonstrates American democracy as unfair. He speaks about American democracy without doubt of its efficiency yet does not trust India to make its political decisions without U.S. intervention. Although Saund suggests his goal is to unite the East and West, the coverage of his tour encourages us to question the results of Saund’s devotion to American democracy and to understand his intentions to be a product of Cold War tensions, favoring the United States’ position.