When Congressman Dalip Singh Saund arrived in Vietnam in 1957, the country was effectively split along the 17th parallel in a highly contested and militarized divide. In the photo above, Saund is pictured with other U.S. officials in the United States Information Service (USIS) Library in Saigon assessing damage caused by a bomb, allegedly part of a “terrorist plan” against U.S. personnel in Vietnam. Now known as Ho Chi Minh City, the capital of South Vietnam was the focal point of the Tet Offensive of 1968, one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. The photographs contextualize Saund’s visit in the rising unrest around U.S. presence in Vietnam in the mid-1950s.

Saund plays a role here in facilitating the United States’ favorable relationship with a Southeast Asian country facing threat from Communist forces. This photograph reveals the dynamics of imperialist paternalism between the knowledgeable Westerners advising the Vietnamese people on how to resolve their own affairs, even if the bombing was the direct result of their involvement. The Western trio are stern and professional, listening intently and ready to use the information they gather to concoct a strategy. There is a marked contrast between the Vietnamese people who are spatially set apart from the conversation surrounding the bombing and the Western group. Despite the gaping hole in the wall, the rest of the room looks copacetic. Boxes and bags are neatly stacked against the walls and the library workers sit at the table working on what looks to be business as usual. If it were not for the hole in the wall or the presence of the American men, the photo would just be a record of a normal day at the library. The relatively calm atmosphere in a building damaged by a bombing implies that such occurrences are, if not commonplace, at least expected. The Vietnamese people seem almost indifferent to their circumstances. The scene brings to mind adults who talk business while children who are unable to handle their own affairs stand aside. Furthermore, the Western trio are set apart by their Westernized, and apparently more professional, dress that visually establishes them as more adultlike. The photograph makes visible the inherently paternalistic nature of American imperialism that obscures its colonial control over foreign nations as a benevolent concern for their development as a democracy.

The United States is an empire that has been reluctant to claim its title. To obscure this history, it has put in place mythologies that reframe blatant neocolonial tactics as a project to spread democracy that instead takes on the tone of patriarchal benevolence. Like any empire, these myths are sold not only to the ruling class, who believe in their own righteousness, but also to subaltern nonwhite citizens under their subjugation. Saund, in his capacity as congressional representative for what was then California’s 29th congressional district, embarked on a global tour in 1957 to spread goodwill as a living symbol of American democracy. Saund’s status as the first Asian American member of Congress was mobilized for this tour as a means of counteracting Communist “propaganda.” During the Cold War, the Soviet Union’s most effective counter to the United States’ conception of itself as a fair and equal democracy was the exclusionary racial policies in the United States. Attention drawn by segregation and the continued influence of Jim Crow policies in the United States tarnished its image but most importantly made foreign countries skeptical as to U.S. dedication towards upholding democratic principles. Saund’s identity therefore serves as an embodied testament to the fairness of American democracy and plays a role in ameliorating the damage caused to the U.S. reputation. It was particularly important for the U.S. to establish good relations with Southeast Asia during this time to ensure their participation in an emerging global market over which the U.S. would reign superior. By perpetuating the myth that American democracy is a neutral society that allows for non-Western people to rise to positions of power, Saund is a living symbol of hope that countries of the Global South can aspire to a similar successful trajectory within the context of an emerging global imperialism.

Therefore, Saund’s ethnic identity complicates the traditional divide between East and West, white and nonwhite, as proof of American democracy fulfilling its promises. He stands with his white companions as an equal within the interplay of racial dynamics. Here, the marked difference between the white imperialist figure and the nonwhite Other are visually expanded to include Saund—an imperialist figure with whom other Asian subjects can identify, who operates in excess of that binary. Saund’s paternalism takes on the function of the imperialist who promises equality to Asian subjects, but in being nonwhite he contributes an extra layer of compulsion by eliciting compliance in the guise of creating solidarity.

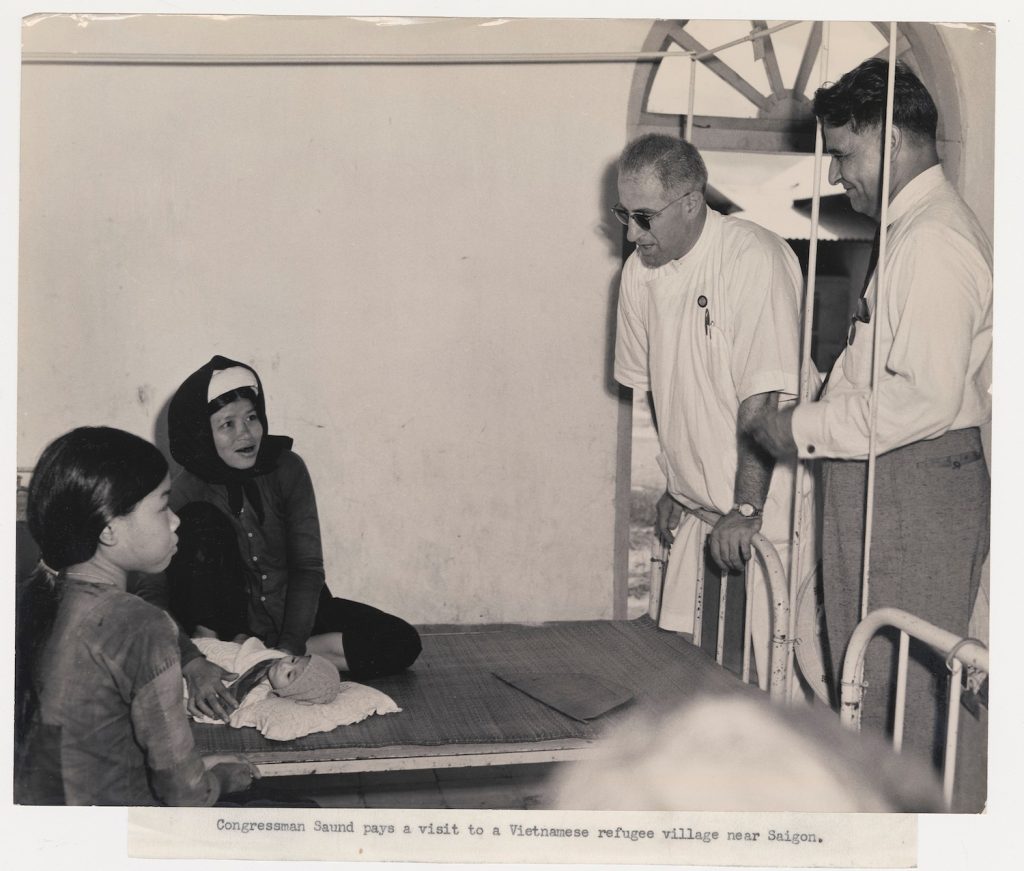

This photo is taken at a Vietnamese refugee village near Saigon, indicating that the family depicted was likely displaced due to the guerilla campaigns that preceded full-scale military action. It becomes obvious why Saund would choose to visit the refugee camps during his limited time in Vietnam. Whether he does so intentionally or not, his presence as a Western man, especially as one who rose from the ranks of the Asian immigrants, cements the cultural imaginary of the United States within Vietnamese consciousness. He is not only a kind man from a richer, developed world that wants to extend its aid to people in need. He is one who proves that this new world is open to Asian subjects like themselves. Saund works directly to sell the concept of benevolent American aid by proving that Asian subjects can ostensibly flourish under American imperialism.

However, his benevolence is not enough to bridge the gap between him and all the Asian subjects of the world who haven’t attained his position. Saund’s formal posture implies that he is not visiting the refugee family because he belongs there, but that he is there for some purpose other than leisure. His obviously different apparel clearly demarcates his position as a foreigner but one who is professionally dressed and therefore knowledgeable. His smiling expression gives one the impression that he cares for the family and would like to extend his kindness towards them. His smile is not a smile that one offers to close friends and family but the smile of someone who is cordially friendly. This distance is made spatially apparent by the large portion of empty space in the center of the photograph. Saund and his companion do not sit on the bed with the family. The distance between the Western men and the Vietnamese family becomes analogous to the unbridgeable gap between their respective worlds. Although Saund comes from an Asian country, it is quite clear whose interests he works for. He is not there just to be acquainted with the Vietnamese but to assess the state of South Vietnam to ensure that U.S. interests are advanced.

Here we see a mother, a daughter, a baby, and a very obvious lack of father figure to complete the nuclear family. The father could be dead, missing, or just not included in the picture; nonetheless, the present absence of the patriarchal figure becomes almost palpable as the eye scans two female figures and one infant figure. In addition, Saund’s upright position visually contrasts that of the sedentary family whose sitting position becomes emblematic of their lack of mobility. Therefore, the smiling Saund visually fills in the gap where one maybe be looking for the father figure. He serves as the missing patriarch, contrasting the lack of agency established by the family’s surplus of femininity, ethnic identity, refugee status, and lack of social mobility. He comes to the family in a moment of distress and symbolically offers them the hand of American paternalism, but a hand that is Asian like their own. Here, Saund is a patriarchal imperialist figure with whom Asian people can identify. He represents American democracy’s promise to abolish the Communist threat and establish a globalized capitalist system in which Asian countries are welcome to participate. The baby in the photo represents the family’s vulnerability to such mythologies, but it also represents the limited hope afforded to them by Saund: that if the United States wins the Cold War, that baby will grow up in a world where it can someday be the next Asian person who makes it within the Western world.

¹ Mary Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy, Chapter 3 “Fighting the Cold War with Civil Rights Reform.”