To some extent, my Asianness has always felt performative. I have measured Asian identity by cultural standards that I saw as contrary to American culture, joking with other Asian American friends about being “whitewashed” and “Americanized,” then turning to laugh with non-Asian friends about “how Asian” my home-cooked Korean lunches made me look. When it came to understanding Asian American communities, I had taken the jokes of my childhood for objective truth. Of late, however, recent attacks and harmful rhetoric have had me closely examining my identity as an Asian American in ways I never had before. While the violence and scapegoating that have occurred since the start of the 2020 COVID pandemic shed light on much of the thinly-veiled hatred that has been simmering under the surface in the United States, there has also been a surge of cross-cultural, intersectional activism against anti-Asian discrimination. This sociopolitical moment has given me a chance, perhaps for the first time in my life, to truly reflect on what my Asian American identity means to me, to deconstruct some of my assumptions about my community, and to stand in solidarity with other Asian communities. It is in this context that Dalip Singh Saund’s life and legacy becomes not only personally relatable but all the more relevant to current discourse. While Saund’s private reflections on his identity remain a mystery, his words and actions display the complexity of interactions between his racialized “Asianness,” his Indian ethnicity, and his attempts to assimilate into the structure and culture of the United States.

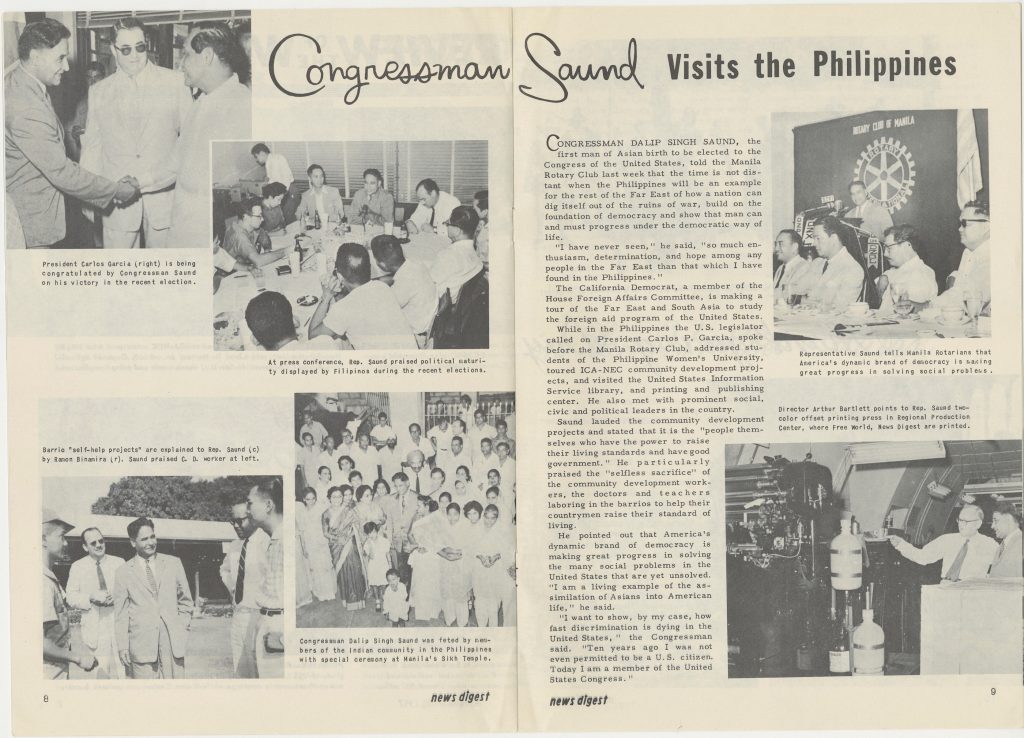

A News Digest article, published by U.S. information services in Manila, featuring Saund’s 1962 trip to the Philippines, illustrates the way Saund’s many identities are simultaneously intertwined and at odds with each other. In the U.S., Saund was perceived as unmistakably Indian, often labeled “Indian Congressman” or “Congressman from India” (also the title of Saund’s autobiography). However, for Saund’s tour of Asia, that emphasis on Indian ethnicity was replaced with integration into a collective Asian identity so that he might act as a bridge between America and all of Asia. The article describes Saund as “the first man of Asian birth to be elected to the Congress of the United States” instead of using his typical moniker of “the first Indian Congressman.” The power held by this reframing of national identities into a collective racial identity is evident in a 1956 letter from P. A. Ortiz, writing on behalf of “the voters of Philippine origin in Holtville,” congratulating Saund on becoming the first “man of Asian origin” to be elected to Congress. Saund’s relation to a pan-Asian identity becomes not only a political tool, as used on his tour of Asia, but also a form of empowerment, generating unity for otherwise disparate Asian and Asian American communities.

The News Digest article goes on to quote Saund’s speech to the Manila Rotary Club as well as other remarks he made as he toured the Philippines. The pride that Saund expresses in his speech, as an Asian American Congressman speaking to Asian people, exists as both a form of genuine solidarity and a deliberate political choice. Amidst Cold War tensions, U.S. foreign policy was focused on cultivating allies in the East to push back growing communist influence. By emphasizing his Asian identity, Saund is able to foreground his own life’s trajectory as an admittedly compelling argument in favor of U.S. democracy. Claiming he is a “living example of the assimilation of Asians into American life,” which demonstrates “how fast discrimination is dying in the United States,” Saund carefully performs his “Asian-ness” in an attempt to unify his Asian audiences. He appeals to his own success in order to prove to his audiences that, even as a racialized figure, he has influence in the U.S. government. In focusing on assimilation, Saund uses his racialized Asian identity to further bolster his self-chosen identity as an American. Even as he periodically sets aside specifically Indian labels in order to reach wider Asian audiences, Saund acts as the voice of the U.S. on his tour of Asia, touting “America’s dynamic brand of democracy”—a stark reminder that his tour of Asia has a clear political objective. He attributes his success to American democratic ideals and declining racial discrimination, a strategy he repeatedly employed while addressing Asian countries in hopes of influencing Asian perception of the U.S. and pushing back communist support within Asia.

Even Saund’s praise for the Philippines displays distinctly American influence. Saund predicts that “the Philippines will be an example for the rest of the Far East of how a nation can dig itself out of the ruins of war,” expressing a view of the postwar Philippines that parallels the treatment of Saund’s own story in the media—labeling the Philippines a success story amongst war-torn countries, to be compared with and looked up to, while dismissing the harm decades of colonization has done to the country and its people. This unwavering belief in the idea of social and political mobility is foundational to the construction of the myth of the model minority just beginning to take shape in Saund’s time. While Saund alternatingly takes up the mantles of “Indian Congressman” and “Asian Congressman” in order to engage with Asian audiences, in his interactions he feels more like an outsider, the voice of America rather than a member of those communities.

Saund’s incongruity with his surroundings in Asia is further emphasized by a photo accompanying the News Digest article, depicting Saund at a Sikh temple in Manila with members of the Indian diaspora living in the Philippines. Though Saund stands closely surrounded by temple-goers, the rather stiff positioning (featuring Saund at front and center of the crowd) makes the image feel more like a staged photo-op than a candid moment, emphasizing Saund’s separation from, rather than his commonality with this community. Saund alone wears a full Western suit, a contrast to the sari and kurta-clad women surrounding him. This image reframes the Western-centered idea of foreignness that Saund was forced to contend with in America. While surrounded by members of the Indian community in the Philippines, Saund’s foreignness persists, as a function of the very assimilation into American culture and politics meant to bypass that foreignness in the first place.

In spite of the dissonance in the image, the fact that Saund was sought out by members of the Indian diaspora regardless of his apparent Americanness also serves as a reminder that Indian, Asian, and American are not mutually exclusive of each other. Saund’s complexity lies in the fact that he can never truly bury any facet of his identity, even while he emphasizes one or the other. His attempted assimilation into “American” culture cannot erase the way the world requires the modification of “Indian” or “Asian” to his title of Congressman. Saund’s U.S. cultural assimilation, emphasized in the photo, does not erase the fact that for better or for worse he remains a racialized figure in history—the “Congressman from India,” a title which in and of itself represents the Asian, Indian, and American influences on Saund’s life.

The overwhelming temptation when it comes to analyzing figures like Saund is to expect that their character and their ideals will align with their trailblazing status. Realizing that this isn’t always the case grounds us in reality and illuminates the danger of placing such figures on too high a pedestal. The 2020 election of Kamala Harris as the first U.S. Vice President of Asian descent is testament to the influence Saund and figures like Saund have had on U.S. politics, opening paths to participation for members of marginalized groups. Simultaneously, however, this year’s rampant violence, scapegoating, and the unveiling of long-held hatred against Asian Americans speaks to the persistence of the perception of foreignness that pursued Saund throughout his life. I look at Saund as a figure of dualities: dutiful, yet politicized; standing against discrimination in action while still minimizing its significance in voice; assimilationist, but most remarkable in his difference. His life was a tantalizingly attractive model of the American Dream, yet it demonstrates the deep contradictions that run below its surface. As I reflect on the ways I have been both victim of and complicit in the perpetuation of harmful assumptions and the exploitation of Asian American identity, Saund’s character carries a familiar set of dilemmas that are intimately relatable. In him, I see my grandparents’ fear, my parents’ faith, and my own assumptions. In this way, Saund has my gratitude and sympathy, even as I grapple with the lingering consequences of his story and persona on the Asian American community.