After the 2020 murder of George Floyd as a result of racially motivated police brutality, we experienced a resurgence of the Black Lives Matter Movement: a movement aimed at dismantling structural anti-Black racism. Among protests, petitions, donations, and more, I found myself striving to educate myself. As an Asian American, I began to desire to find ways to not only challenge these effects of structural racism but to seek pathways towards multiethnic solidarity.

The Model Minority Myth, as we now know it, is the systemic belief which typifies Asian Americans as minority individuals with potential for success and assimilation—as living contradictions to racism. This myth is a tool used to divide marginalized groups, developing the proximity of Asian Americans to whiteness and pushing other minority groups, especially African Americans, further away.

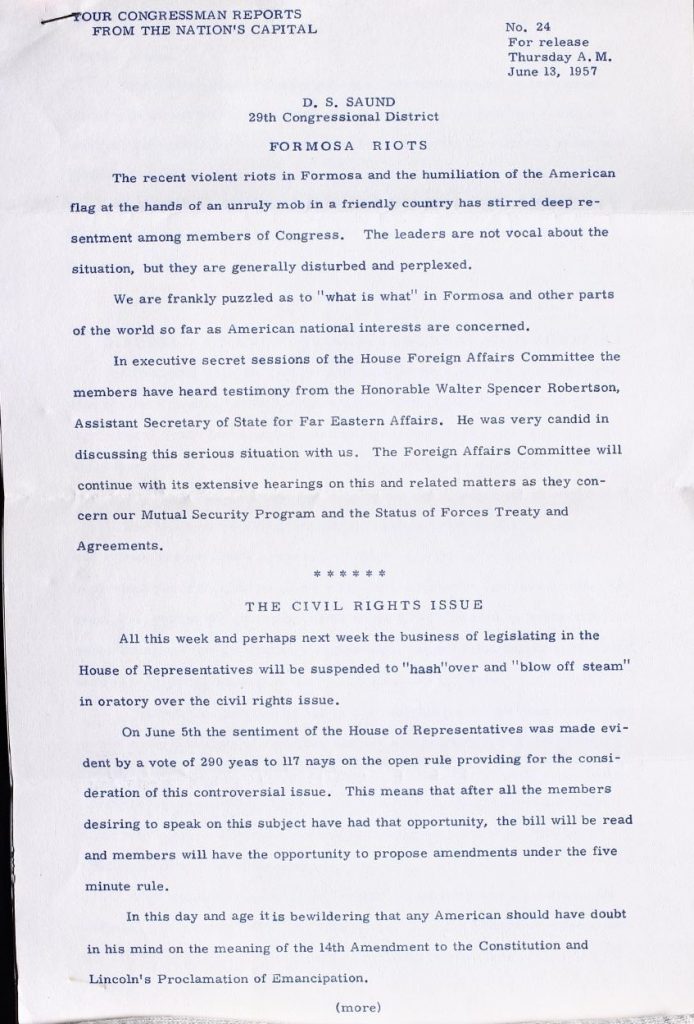

Congressman Dalip Singh Saund provides us with an example of what living in this positionality looked like sixty years ago. Saund was the first Asian American Congressman who served in the 29th District of California from 1957 to 1963. He wrote weekly Congressional Reports to update his constituents on important issues passing through Congress as well as his views and actions regarding them. In a 1957 report, he writes in regards to the Civil Rights Act of 1957, in which President Dwight D. Eisenhower proposed to protect African American voters’ rights by authorizing prosecution of individuals who interfered with the voting rights of U.S. citizens. Because Saund was seen in some ways as a token of diversity for the United States government, he was forced into the role of a marginalized spokesperson who perpetuated what would become the model minority myth. However, Saund is highly supportive of this proposal to protect African Americans. I think it is greatly important that he continued in vocal solidarity with other marginalized groups because it demonstrates how his identity as an Asian American allows him to be so much more than a figure of the model minority.

Saund’s usage of quotation marks when he references the apparent need for Congress to “hash” out and “blow off steam” suggest a disappointment and general dissent from the idea that Congress would need time to discuss and figure out these issues. Saund then writes, “it is bewildering that any American should have doubt in his mind on the meaning of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution and Lincoln’s Proclamation of Emancipation,” confirming his disbelief around this discussion. It is likely that Saund’s role as a target of discrimination makes him more understanding and allows him to take a more radical stance regarding these efforts to ensure voting rights.

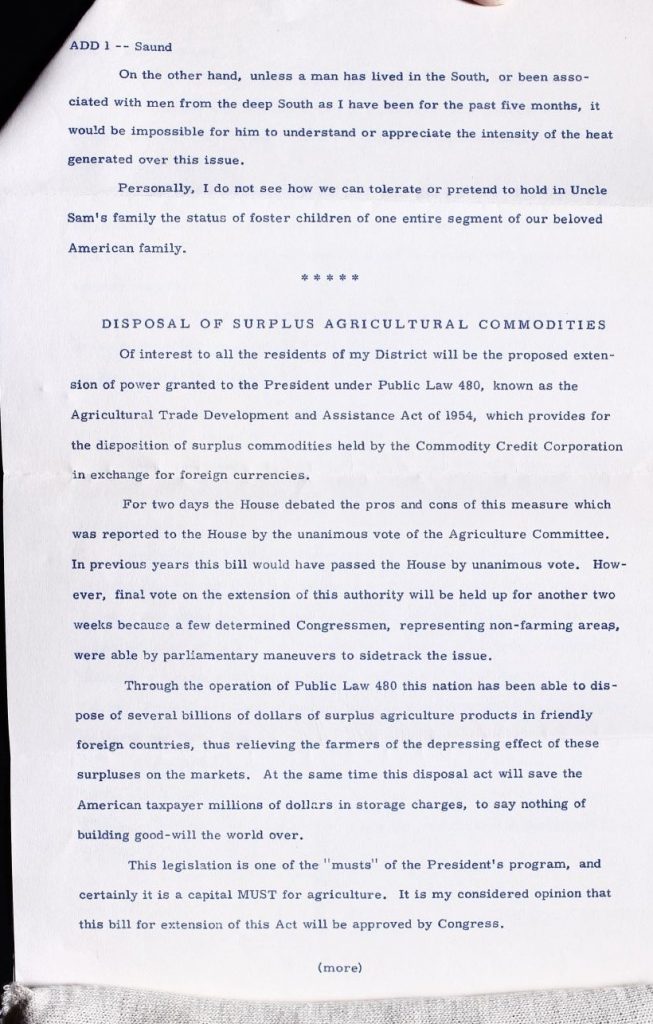

Further, Saund makes a reference to Uncle Sam: “Personally, I do not see how we can tolerate or pretend to hold in Uncle Sam’s family the status of foster children of one entire segment of our beloved American family,” developing a metaphor alongside a metaphor. Not only is Uncle Sam a symbol of America, but he is also a symbol of patriotism. Saund mocks the patriotism that leads to the abandonment of an entire group of citizens. The consideration of partial patriotism is ridiculous. Further, he develops a metaphor of Uncle Sam as an actual Uncle and leans into the familial quality of U.S. citizens. How can we turn our back on our own family? African American people have the right to claim the privileges of U.S. citizenship as much as anyone else.

This said, Saund qualifies these statements by recognizing the difficulty in understanding the experience of African Americans. He says, “unless a man has lived in the South, or been associated with men from the deep South as I have been for the past five months, it would be impossible for him to understand or appreciate the intensity of the heat generated over this issue.” Although Saund does not share the same racial background, he claims to more clearly recognize the struggles Black people face by witnessing them himself. Although he does not say so directly, he might well be aiming to bring his experience in relation to African Americans before the eyes of his constituents, knowing that it is difficult to relate to someone you do not share a position with. In doing so, however, Saund does not explicitly make space for Black voices. By suggesting that by “association” Saund has a grasp on the Black experience, Saund furthers this idea that Asian Americans can speak for African Americans. This is a dangerous position to claim as the voices of Black Americans on these issues are so often silenced. Saund fails to make space for genuine, community expression and instead focuses his response on the reactions of white, Southern politicians. While Saund was a figure who demonstrated multiethnic solidarity, we can learn from his missteps as well.

In his autobiography, Congressman from India, Saund does not lend his story to scenes of discrimination or any seemingly blatant disrespect because of his racial and immigrant identities. This is not to say that he did not experience discrimination, but his writings are not crafted as though discrimination was a primary factor in his American experience. The view of the United States which Saund developed from his experiences with racial discrimination likely makes Saund more understanding of potential of the American Dream despite the reality of racial discrimination. As Saund mentions in his autobiography, he is “a living example of American democracy in practice.” Saund wants African American individuals to both experience the American Dream in the way that he claims to be able to, and he wants to promote policy changes that align with that potential. This leads Saund to his position as a figure of solidarity and a vocal advocate for the Black community.

It is vital that we learn from the successes and faults of figures like Saund even as we continue in his path towards multiethnic solidarity. We can apply these actions to the Black Lives Matter Movement which is resurging right now. From Saund, we can learn to be vocal advocates while also making space for Black voices to be heard. We must consider our own positionality when standing in solidarity with and taking action alongside our Black neighbors.